To gaze at The Dalmore distillery in northeast Scotland on a sunny day seems surreal. The landscape is endlessly gilded, much like the establishment’s brass taps and meticulously buffed exteriors. The hues aptly reflect the region’s most coveted export: whisky.

Inside The Dalmore whisky distillery in northeast Scotland

On the shores of the Cromarty Firth in Scotland, one of the finest whiskies in the world is treated with more reverence than gold.

By Jamie Lafferty - September 24th 2020

The Dalmore has always been made here, just outside the village of Alness, half an hour’s drive from the Scottish Highland capital of Inverness. The Cromarty Firth, an arm of the Moray Firth designated as a special protection area for wildlife, leads out into the unforgiving waters of the North Sea, while inland it nudges in toward the town of Dingwall. This isn’t the land of Scotland’s most dramatic mountains, but with the near-mythic Loch Ness just 35 miles away, it’s where you’ll find some of the nation’s most spectacular waterways.

Founded in 1839 by entrepreneur Sir Alexander Matheson—whose family made their fortune in trade in the Far East—The Dalmore company was taken over in 1867 by Andrew and Charles Mackenzie of Clan Mackenzie, and soon became to be regarded as the producer of one of the finest malts anywhere in the country. While other distillers were focused as much on quantity and consistency as they were on quality, the Mackenzies boldly decided to mature their liquids for twice as long as the industry norm, releasing The Dalmore 12-year-old (still the entry-level bottle) when most rivals were content to bottle at six. When they unveiled a 30-year-old bottle in 1908 no one had seen anything like it.

In all that time since, things on site have largely remained the same. “In terms of the distillery itself and the whisky-making process, nothing much has changed,” says Shauna Jennens, the Dalmore manager of the Brand Home who hosts private tours of the distillery. These can include in-depth tastings, dining events and cigar pairings on site. Away from the distillery itself, accommodation can be arranged at places such as the Fife Arms, the landmark Braemar property where The Dalmore celebrated its 180th birthday last year.

Today, the company is owned by giants of the trade, Whyte & Mackay, who are in turn owned by Emperador Distillers, run by Chinese Filipino billionaire Andrew Tan. “We’ve seen major investment in the last year, with a total overhaul of our visitor center, and our client base has changed now too—we do a lot more private clients and cask sales,” explains Jennens. “The demands of those clients are quite different, but ultimately the whisky is the same.”

Inside The Dalmore, 50-year-old Scott Horner has also been working in much the same way for the last 28 years. By definition, scotch doesn’t allow for much freestyling, but it does require a keen eye for detail. “We handle everything here at The Dalmore—the milling, mashing, tun room and stills,” says the general production operator, keeping an eye on the computer which is in turn monitoring the temperatures and pressures of liquids in various parts of the distillery. These days, much of the process is automated and workers like Horner must keep a steady eye on the numbers.

It used to be a lot more hands on, with fires heating the tuns and workers going through the laborious process of malting the barley. The final product may have been more handcrafted, but it was also less consistent, less valuable and far harder on its producers: The extreme repetition often resulted in a physical disfigurement known as ‘monkey shoulder.’

It’s really after the initial processes that The Dalmore comes into its own. It is eventually aged in at least two wooden casks—one of the techniques which give The Dalmore its distinctively smooth flavor profile. The first state of the maturation begins with American white oak ex-bourbon barrels, sourced from Kentucky to impart flavors of intense vanilla, spice, honey and citrus fruits. From there, it is transferred to sherry casks, sourced from Jerez de la Frontera in Spain. Remarkably, the relationship between The Dalmore and the sherry makers González Byass stretches back 150 years. It’s this exclusive arrangement between the companies that means the Scottish team have access to the best Matusalem casks. It’s those which give the whisky its deep copper color and further enrich the flavor.

By that stage, Horner and his team are drawing samples to be nosed by the master distiller. The Dalmore’s dedication to high-end drams means the brand doesn’t produce a massive amount of whisky: only around 3 million liters per year. In the last 10 years, the company has also stopped contributing to blended whiskies around the country to focus exclusively on its own product. As Horner puts it: “Now all we make is The Dalmore for The Dalmore.”

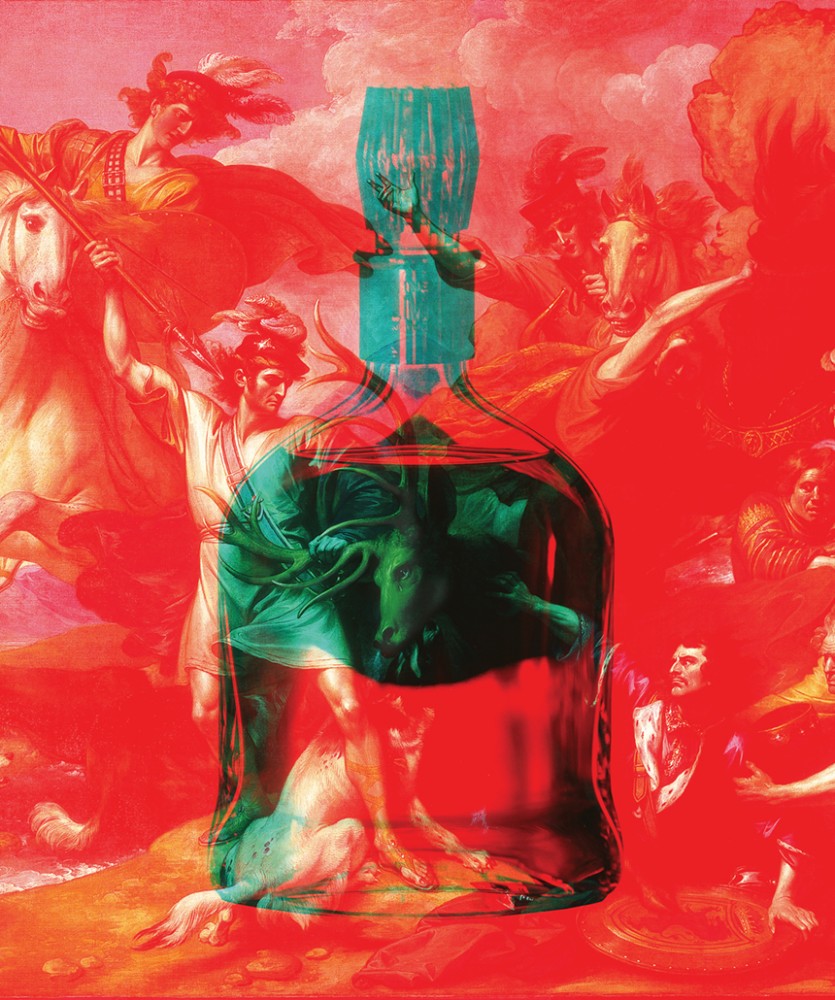

Of all its venerated products, The Dalmore King Alexander III is arguably the most complex of all the whiskies, aged in ex-bourbon casks, Matusalem oloroso sherry casks, Madeira barrels, Marsala casks, port pipes and cabernet sauvignon wine barriques, providing the liquid with a dizzying array of flavors. It’s far from being the brand’s most expensive, however.

Potential owners and investors can consult with Jennens to decide whether or not to invest in an entire cask of their favorite variety. There are options to have it bottled immediately, or laid down for longer, which in this business can mean decades. Those not willing to wait can have it decanted to customized bottles. While design elements can be selected from The Dalmore portfolio, the distinctive royal stag emblem remains prominent on every bottle (legend has it that during a hunt, Scots King Alexander III was saved from a charging stag by Colin Fitzgerald, founder of Clan Mackenzie).

There are also investors who buy bottles with no intention of ever trying the whisky. While some people choose to invest in art, there’s always a risk in appreciation; much of that is removed with whisky which, as a general rule, increases in value the longer it stays in the barrel. This is despite the angel’s share, the alcohol which slowly evaporates as the whisky ages in barrels. The Dalmore is careful to regularly measure the exact alcohol content, to ensure that it can still legally be called scotch. Managed properly, as it is here, a carefully selected cask of scotch can see its value soar over the decades. The oldest barrel currently held on site is almost 70 years old, placing its potential value in the millions. In 2017, a bottle of The Dalmore 62-year-old sold at Christie’s for $150,000, and just last year a unique bottle named L’Anima went for $141,000.

The fate of such drams is unlikely to ever involve the pleasure of being consumed. “Well, it depends. For example, our 21-bottle Constellation Collection, we hear of things such as customers drinking one, then keeping the rest,” explains Jennens. “When you have something like the Trinitas, where only three bottles were made, then no, they wouldn’t touch that. Something like that is worth much more left in the bottle.” While this is likely to be in a bid to preserve the value of the liquid within, it’s just as easy to believe that bottles carrying such investment of time and craftsmanship deserve to be left untainted, like any piece of great art.

Related articles

-

Go to articleInsight

Editor's Letter

By Pierre Beaudoin - October 26th 2024

A Message from Pierre Beaudoin Chairman of the Board, Bombardier

-

Go to articleInsight

Introducing The Aviator Lounge in Monaco

By Rachel Ingram - October 24th 2024

Behind the scenes at Bombardier’s multifaceted meeting space

Latest articles

-

Go to articleFeatured Aircraft

Super Powered

By Christopher Korchin - October 24th 2024

The Bombardier Global 7500 and the Bombardier Global 8000 are the industry’s most spacious ultra-long-range business jets. But they also excel in performance on short runways, opening up a world of prized destinations.

-

Go to articleProfiles

Family Affair

By Stephen Johnson - November 29th 2024

From a snowmobile manufacturer to a global leader in business aviation, Bombardier’s enduring legacy is built on innovation and family values.